Introduction

This insight paper outlines fathers' and partners' access to and utilisation of parental leave in Australia. It canvasses the literature on the benefits of parental leave for men across three areas: benefits for families, mothers, fathers & children; impact on gender equality, and benefits for organisations.

Table of contents

- Key findings

- About parental leave policies in organisations

- What is parental leave and why does it matter?

- Australia's policy architecture

- Employer paid parental leave policies in Australia

- Benefits associated with parental leave

- Challenges for men and partners in the uptake of parental leave

- The business case for parental leave

- Conclusion

- References

Downloadable PDF version:

Key findings

- In Australia, organisations are moving towards gender-neutral parental leave policies, offering equitable parental leave for all parents.

- Organisations that provide strong parental leave schemes are more likely to enjoy better recruitment and retention. These policies send a message that the organisation supports gender equity and that employees with families are valued.

- The availability of paid parental leave for each parent fosters an equal division of unpaid care and improves family work-life balance.

- The greatest benefits to individuals, organisations and society are associated with parental leave schemes that are flexible and generous.

- Research has found that working long hours (45 hours or more) is the strongest predictor of not using all paid leave entitlements and men dominate this group, fulfilling traditional masculine full-time worker expectations.

About parental leave policies in organisations

In Australia, organisations are moving towards gender-neutral parental leave policies, offering equitable parental leave for all parents. This means that organisations are recognising the demands of changing family structures and by using gender-neutral language, these organisations recognise that both parents are responsible for the upbringing of children.

Definitions

| Parental leave: | Entitlement for parents to care for young children (either together or one parent at a time). In some cases until the child reaches two or three years of age. |

| Maternity leave: | Employment protected individual leave entitlements for mothers. |

| Primary carer's leave: | Employment-protected leave taken by the primary person who has the majority daily responsibility for caring. Only one person can be a child’s primary carer on a particular day. |

| Father/partners/secondary carers leave: | Employment-protected leave for the father or partner, such as paternity leave, individual entitlements to parental leave and any weeks of shareable parental leave that are reserved for use by the father or partner only. |

Source: (OECD, 2016)

What is parental leave and why does it matter for fathers and partners?

Around the world, government and industry have turned their attention towards matters of men and their access to parental leave (Amin et al., 2016; Petts et al., 2018; Karu & Tremblay, 2018). The design, or architecture, of parental leave schemes vary markedly, according to the country and their political histories and cultural contexts. Schemes differ in objectives, eligibility, duration, payment level and funding.

The literature shows that parental leave can serve several purposes: building gender equality, promoting bonding with babies, allowing for the care of partners and other children. Parental leave supports gender equality by helping to facilitate equitable sharing in the care of young children. It can build stronger bonds between fathers and children, especially during a child’s early years.

Yet uptake by fathers and partners tends to remain low because of barriers relating to income, organisational stigmas and traditional gender norms (Coltrane et al., 2013; Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2019; Patnaik, 2018, as cited in Théboud and Halcomb, 2018; Kalb, 2018; Baxter, 2019). The highest rates of utilisation are in countries with designated schemes for men that provide high income replacement levels as well as incentives for fathers to take the leave, for example the Nordic countries and the Canadian Province of Quebec (Feldman & Gran, 2016; Harvey & Tremblay, 2018; Karu & Tremblay, 2018).

The increased participation of women with children in paid employment in Australia means that 63% of fathers with dependent children now have a partner in the paid workforce (Pocock, Charlesworth and Chapman, 2013). Australian men are also increasingly interested in being active and engaged fathers (Baxter, 2014; Hill, Baird et al., forthcoming). Yet existing research finds that Australian men are less likely than women to have or to request access to parental leave, and they are more likely to be refused or penalised when they do (Chapman, Skinner and Pocock, 2014).

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2017) data show that one in twenty Australian fathers use primary carer’s leave. While mothers are more likely to use primary carer’s leave, fathers and partners make up 95% of all secondary carer’s leave claims (ABS, 2017). Administrative data from the federal Department of Human Services (2018) in Australia show that the ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ DaPP scheme had 95,000 successful claimants in 2016-17, and 93,000 in 2017-18. An estimated 25-30% of fathers accessed DaPP in 2017-2018 (ABS, 2017). The review of the Australian government’s paid parental leave scheme showed fathers and partners are more likely to use their annual leave to take time off to care for children. This is likely because it is paid at full wage-replacement, while DaPP is paid at the minimum wage (Martin et al., 2014). Fathers and partners in the UK exhibit the same pattern (Koslowski & Moran, 2018). To support childcare responsibilities, fathers in Australia are more likely to work flexibly or to work from home (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2019; Baxter, 2019).

Australia’s policy architecture

In Australia employees are entitled to both unpaid and paid parental leave.

Unpaid parental leave

Under the NES (National Employment Standards) provision of the Fair Work Act, 2009 employees (including long term casual employees) with 12 months or more of continuous service with an employer are entitled to take up to 12 months of unpaid parental leave from work, with the right to request an additional 12 months. This is equally available to fathers and mothers who meet the eligibility requirements. This unpaid parental leave can be taken when:

- an employee gives birth,

- an employee adopts a child under 16 years of age

- an employee’s spouse or de facto partner gives birth,

The legislation guarantees that leave takers can return to the same position they held before they commenced their period of parental leave. If their position no longer exists, the employee should be transferred to a position that they are suitably qualified for and which is nearest in status and pay to their pre-parental leave position.

Paid parental leave

Australia’s national Paid Parental Leave scheme was introduced on 1 January 2011, following the introduction of the Paid Parental Leave Act 2010. Under this scheme, eligible working parents receive tax-payer funded pay (set according to the National Minimum Wage) for the duration of their leave.The Paid Parental Leave scheme provides two payments: Parental Leave Pay (PLP), and Dad and Partner Pay (DaPP).

The Parental Leave Pay scheme provides the eligible primary carer (usually the mother) with 18 weeks Parental Leave Pay at the National Minimum Wage. Under certain circumstances this can be shared between both parents. This payment is tax-payer-funded but is usually provided by employers to long- term employees in their usual pay cycle. Parents who do not receive the Parental Leave Payment from their employer or who do not have an employer, receive the payments directly from the Department of Human Services.

On 1 January 2013, the Paid Parental Leave scheme was expanded to include a two-week payment for working fathers or partners. This is called Dad and Partner Pay. DaPP provides dads, or partners caring for a child, with up to two weeks government-funded pay. This is also paid at the rate of the National Minimum Wage. Dads, or partners, must be on unpaid parental leave (see above) or not working to receive the payment.

Both PLP and DaPP can be complemented by employer schemes, that is, employers can provide additional parental leave pay, either through company policy or enterprise agreements. Superannuation is not included in either the Australian Paid Parental Leave scheme or Dad and Partner Pay. However, existing legislation does not prevent individuals from making voluntary superannuation contributions, or employers from contributing.

Employer paid parental leave policies in Australia

In Australia, 47.8% of employers with 100 or more employees offer paid primary carer's leave (WGEA, 2018).

Availability of employer-funded parental leave

The availability and length of paid parental leave provided by employers varies across industries and organisations. WGEA refers to primary carers' leave data (2018) which shows that in 2017-18, the average length of paid primary carer's leave was 10.3 weeks across all industries.

- Public Administration and Safety had the shortest average primary carer's leave (6.8 weeks), followed by Accommodation and Food Services (7.1 weeks) and Health Care and Social Assistance (7.9 weeks)

- Mining had the longest average primary carer's leave at 12.9 weeks, this was closely followed by Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (12.6 weeks), Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services (12 weeks), Financial and Insurance Services (12 weeks) and Education and Training (13 weeks).

Importantly, given that fathers and partners disproportionately represent secondary, rather than primary carers, across all industries, 41.8% of employers offer secondary carer's leave. Amongst all industries:

- Education and Training is the most prevalent 76.1% of employers), followed by Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services (73.9%) and Financial and Insurance Services (70.5%)

- Public Administrations and Safety have the highest average minimum number of weeks offered for secondary carer's leave (2.3 weeks), followed by Financial and Insurance Services, Other Services and Wholesale Trade (all at 1.9 weeks)

- The lowest minimum number of weeks was Accommodation and Food Services (1.2 weeks), followed by Construction, Retail Trade and Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (all at 1.3 weeks).

Utilisation of employer-funded paid parental leave

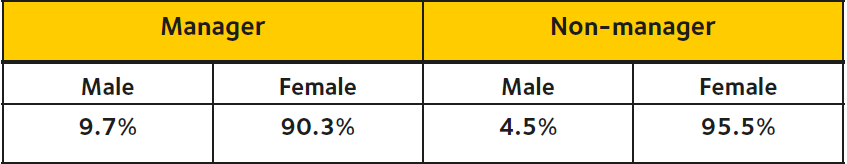

Employer-funded parental leave in Australia is largely utilised by women (see Table 1). However, the share of men using employer-funded parental leave is higher than the share of men using government-funded paid parental leave. This is likely to reflect the relative generosity and flexibility of employer-funded parental leave schemes. Case studies show:

- Employers have a key role in normalising fathers/partners utilisation of parental leave and flexible working to meet caring requirements;

- A supportive workplace culture as well as leadership support is key to increase fathers’ or carers’ uptake of parental leave.

Table 1: Employer-funded primary carer’s leave utilisation, 2017-18

Source: WGEA (2018), Agency reporting data (2017-18 reporting period)

Availability of employer-funded superannuation top-ups

In Australia, employers are not required to make superannuation contributions for employees on paid parental leave, but they can and do. Notable organisations that include superannuation payments in their parental leave policies include: NGS Super, HSBC Australia, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, ANZ, NAB and Westpac. A number of organisations are also providing superannuation payments in addition to parental leave benefits, including Viva Energy, Dexus and Diageo.

Benefits associated with parental leave

The research shows that when parental leave is taken by men, it is beneficial to individuals, families and organisations. However, parental leave offerings with the greatest benefit are those that are: paid at a high wage-replacement rate; longer in duration; and designated specifically to fathers and partners.

Benefits to mothers

Mothers benefit when fathers and partners take parental leave around the time of birth as they have more time to recuperate after childbirth receive more emotional support and experience less stress (Porter, 2015; Heymann et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2017). When fathers and partners take parental leave, they are more likely to participate in ongoing childcare and other unpaid household responsibilities (Norman, Fagan and Elliot, 2017). This leaves women with more time to spend on paid employment, facilitating greater economic independence and higher household incomes (Thor, Arnarson & Mitra, 2008). Partner support also leads to a smoother transition back to work and fewer experiences of child and flexibility related stigma in the workplace. Overall, father or partner involvement in childcare may provide mothers with a stronger sense of well-being, heightened relationship satisfaction and an enhanced ability to balance work and life commitments (Norman et al., 2018).

Benefits to fathers and partners

Fathers’ involvement in childcare has been linked to improved well-being, happiness and increases their commitment to family (Norman et al., 2018). Fathers have also been found to benefit through a reduction of risky behaviours such as smoking and alcohol consumption (Chan et al, 2017). They report learning new skills such as prioritising, role modelling and compassion which they transfer to the workplace (Harvey & Tremblay, 2018).

Benefits to children

Health-related benefits accrue to children as fathers’ and partners’ uptake of parental leave is linked to mothers’ decision to breast-feed (Porter, 2015). When fathers take parental leave, children enjoy better relationships with them, increased father involvement over their lifetime and stronger school performance (Porter, 2015; Heymann et al, 2017). Children also benefit from higher household incomes as a result of both parents working and increased access to better health services and education experiences.

Benefits to households

Households can benefit through a shift in gender norms and through stronger parental relationships (Norman et al., 2018). The availability of paid parental leave for each parent fosters an equal division of unpaid care and improves family work-life balance. Additionally, higher household incomes and increased economic security are associated with fathers’ use of parental leave (Andersen, 2018).

Promoting gender equality

Father’s or partner’s use of parental leave contributes to gender equality in several ways. At home, men’s use of parental leave is associated with a more equal distribution of unpaid work and changes in traditional gender norms (Karu & Tremblay, 2018). In the workplace, equal uptake of parental leave between women and men can also moderate discrimination in the hiring process by reducing employers’ reluctance to hire, retain and promote mothers (Porter, 2015), and childless women of childbearing age due to assumptions about their need to take time off for care. Finally, men’s use of parental leave contributes to future gender equality with daughters of working mothers more likely to work and to earn higher wages (McGinn et al., 2018). Further, children who have parents that model gender equality are more likely to carry these new norms forward.

Benefits to organisations

When fathers and partners take parental leave, organisations report better recruitment, retention and promotion rates, leading to stronger performance and productivity outputs (Porter, 2015). Paid leave benefits send a strong signal of an organisation’s commitment to employees, and thus these benefits can help to attract and retain top talent (Rau and Williams, 2017). Indeed, Australian research finds that parental leave is a key driver of employment decisions and job performance for both women and men, including young men, male mangers, men approaching retirement, and most especially young fathers (Diversity Council of Australia, 2012).

Parental leave can also deliver economy wide benefits through enhanced women’s workforce participation. A World Bank study in the developing world found a 6.8% increase in female workers at firms with mandated parental leave. There are also potential benefits to economies, with McKinsey Global Institute (2016) estimating a $28 trillion dollar increase in global GDP by 2025 if women and men’s workforce participation rates were identical.

Challenges for men and partners in the uptake of parental leave

Although access to paid parental leave provides many benefits, uptake by fathers and partners is typically quite low. This is due to the challenges fathers and partners face in accessing parental leave.

Gender norms

Gender norms which assume women do the majority of childcare may dissuade fathers from taking parental leave due to the perception that unpaid work, is ‘women’s work’ (Coltrane et al., 2013; Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2019). Studies of parental leave suggest that men are more likely to utilise care-giving leave when there is strong organisational support and encouragement (Patnaik, 2018, as cited in Théboud and Halcomb, 2018).

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap also poses barriers as loss of family income has less impact when women, who on average earn less than men, take parental leave (Kalb, 2018; Walsh, 2019; Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2019; Koslowki & Moran 2019). Moreover, there is evidence that men who take time off for family reasons earn substantially less over time compared to those who do not (Coltrane et al., 2013).

The “ideal worker” stereotype

Research has found that working long hours (45 hours or more) is the strongest predictor of not using all paid leave entitlements, and men dominate this group, fulfilling traditional masculine full-time worker expectations. Through an analysis of the Australian Work and Life Index, Skinner and Pocock (2013) found that 60% of full-time employees did not take their full annual leave entitlements. Many people who work long hours report struggling with work-life balance, in areas such as family, nutrition and exercise (Skinner & Pocock, 2013). Their failure to make use of their leave is likely to compound these problems.

Workplace culture

Organisational support is key to encouraging or discouraging employees to take parental leave. A study of Canadian and American fathers with access to parental leave found that employer and colleague perceptions were the most common barriers (Rehel, 2014). Studies in Switzerland and the UK found that uptake of parental leave is higher in male- dominated team contexts, likely due to role-modelling by fathers who took leave (Valarino & Fauthier, 2016; Koslowski & Moran, 2019). These findings highlight the importance of organisational cultures that support access to and the taking of leave entitlements.

Need for incentives

Fathers are more likely to take parental leave when there is incentive to do so (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2019). Such incentives include father quotas (use- it- or-lose-it policies that reserve some parental leave exclusively for fathers), high wage- replacement rates, and financial bonuses, as evidenced through the experience in Nordic countries and the Canadian province of Quebec, which exhibit the highest rates of uptake globally (Feldman & Gran, 2016; Harvey & Tremblay, 2018; Karu & Tremblay, 2018; Rehel, 2014; Kalb, 2018). Patnaik (2019, forthcoming) in examining the Quebec Parental Insurance Program finds that the use of ‘daddy quotas’ increased fathers’ participation by 250%, primarily through higher benefits in tandem with weeks that were explicitly framed as ‘daddy’- only. Furthermore, Patnaik (2019, forthcoming) finds that it is possible for policies such as ‘daddy quotas’ to not only induce short-term changes in behaviour but to also have an enduring impact on changing household dynamics.

The business case for parental leave

Research suggests that there is a strong business case for paid parental leave as a cost effective means of retaining valued staff and provides considerable benefits for organisations and employees. The availability of paid parental leave links to an increase in job satisfaction as well as an increase in employee productivity and loyalty. Paid parental leave benefits organisations by:

- Increasing the number of employees returning to work after parental leave

- Reducing recruitment and training costs

- Improving staff morale and productivity

- Providing a cost-effective means of retaining skilled staff

- Improving organisational efficiency through the benefits of long service, for example, institutional memory, industry knowledge, networks and contacts.

Organisations can undertake the following actions to address challenges that arise when implementing a parental leave policy or encouraging men to take up this leave:

- Increase awareness: Encourage the uptake of leave through their culture, policy and support for employees. Employees should be made aware of all options that are available to them, including government schemes and organisational leave policies Organisational support for the use of parental leave by men can be displayed through promoting the experiences of male role models who have taken leave and returned to work without consequence.

- Economic rationale and benefits: Ensure that business leaders understand the economic benefits and rationale for establishing a paid parental leave policy. Given that offering paid leave increases morale and productivity, this will likely outweigh the costs of replacing employees who leave, training a new employee (Investing in Women, 2019) and the loss of intellectual capital.

- Project continuity and coverage: Organising in advance for planned and unplanned leave and providing incentives helps to reduce the impact of concerns about difficulty hiring short term replacement staff and project continuity.

- Perceptions of equality: The key to realising the benefits of parental leave is ensuring that all employees have equal opportunity to access it. Offering parental leave to all employees regardless of gender or employment status ensures that the leave is perceived as equal for all employees.

The Australian Fair Work Ombudsman suggests a number of best practice guidelines to implement parental leave. These include understanding employee needs, publicising policies, creating communication and transition plans, discussion of flexible work options (job sharing, working from home) upon returning to work, offering flexible options for taking leave, and providing support for children at work such as access to the workplace, carer’s room, and childcare facilities (Fair Work Ombudsman, 2016).

Conclusion

Paid parental leave provides many benefits to fathers, mothers, children, organisations and society. Yet uptake of parental leave by men is still low in Australia, with only one in twenty fathers taking leave under the Australian Paid Parental leave scheme (ABS, 2017). Research shows that fathers and partners are more likely to take parental leave if organisations have a supportive workplace culture and if leadership supports fathers' and partners' utilisation of parental leave. Employers have a key role in normalising fathers and partners utilisation of parental leave and flexible working to meet caring requirements.

References

Full reference list

-

OECD (2016), Family database, Parental Leave Systems, OECD Social Policy Division 28, Retrieved from: <http://www.oecd.org/els/family/PF2_4_Parental_leave_replacement_rates>.

-

Amin, M. et al. (2016), “Does Parental Leave Matter for Female Employment in Developing Economies?” Work Bank Group, Last accessed 7 May 2019, <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/124221468196762078/pdf/ WPS7588.pdf.

-

Arnarson, B.T. and Mitra, A. (2010), “The Parental Leave Act in Iceland: Implications for Gender Equality in the Labour Market.” Applied Economics Letters, 17.7: 677–680.

-

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017), One in 20 dads take primary parental leave, viewed 27 May 2019, <https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4125.0~Sep% 202017~Media%20Release~One%20in%2020%20dads%20take%20primary%20parental% 20l eave%20(Media%20Release)~11>.

-

Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2019), “Bringing up baby: Fathers not always able to share the load.” Available at: https://aifs.gov.au/media-releases/bringing- baby-fathers-not- always-able-share-load.

-

Baxter, J. (2019) “Fathers and work: A statistical overview.” Australian Institute of Family Studies. Available at: https://aifs.gov.au/aifs-conference/fathers-and-work.

-

Baxter, J (2014) ‘Gender role attitudes within couples, and parents' time in paid work, child care and housework’ The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2014, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

-

Blum, S., Koslowski, A., Macht, A. and Moss, P. (2018), International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2018. Available at: http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/.

-

Budig, M. J. and England, P. (2006) ‘The Wage Penalty for Motherhood’, American Sociological Review. doi: 10.2307/2657415.

-

Chan, Ko Ling et al. (2017), “Association Among Father Involvement, Partner Violence, and Paternal Health: UN Multi-Country Cross-Sectional Study on Men and Violence.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52.5, 671–679.

-

Chapman, J., Skinner, N., and Pocock, B. (2014), “Work–life Interaction in the Twenty- First Century Australian Workforce: Five Years of the Australian Work and Life Index.” Labour & Industry: a journal of the social and economic relations of work, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 87–102.

-

Chua, A. (2017), “New Fathers Reluctant to Take Parental Leave”, Human Resources Director, accessed 12 June 2019 at <https://www.hcamag.com/au/specialisation/diversity-inclusion/new- fathers- reluctant-to-take-parental-leave/150856>.

-

Coltrane, Scott et al. (2013), “Fathers and the Flexibility Stigma.” Journal of Social Issues, 69.2: 279– 302.

-

Department of Human Services (2018), 2017-18 Annual Report, Commonwealth of Australia 2018, available at: https://www.humanservices.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018/10/8802-1810- annual- report-web-2017-2018.pdf.

-

Diversity Council of Australia, (2012), Men Get Flexible! Mainstreaming flexible work in Australian business, Diversity Council Australia: Sydney.

-

Ernst & Young, (2017), Viewpoints on paid family and medical leave: Findings from a survey of US employers and employees. Available at:<https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:gtuhuSsJMpwJ:http s://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-viewpoints-on-paid-family-and- medical-leave/%24FILE/EY- viewpoints-on-paid-family-and-medical- leave.pdf+&cd=8&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=au&client=safari#3>.

-

Feldman, K, and Gran, B, (2016) “Is What’s Best for Dads Best for Families? Parental Leave Policies and Equity Across Forty-Four Nations,” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 43.1: 95– 119.

-

Gerson, K. (2017) ‘There’s No Such Thing as Having It All: Gender, Work, & Care in an Age of Insecurity.’ In Gender in the 21st Century: The Stalled Revolution and the Road to Equality, edited by Shannon N. Davis, Sarah Winslow, and David J. Maume. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

-

Hartge-Hazelman, B. (2018), ‘More employers are paying superannuation during parental leave but many women are still missing out’, Smart Company, 13 July, accessed 27 May 2019, <https://www.smartcompany.com.au/finance/superannuation/more-employers-are- paying- superannuation-during-parental-leave-but-many-women-are-still-missing- out/>.

-

Harvey, V, and Tremblay, D. (2018), “Parental Leave in Québec: Between Social Objectives and Workplace Challenges,” Community, Work & Family, 1–17.

-

Heymann, Jody et al. (2017) “Paid Parental Leave and Family Wellbeing in the Sustainable Development Era.” Public Health Reviews, 38.1: 21–21.

-

Hodges, M. J. and Budig, M. J. (2010) ‘Who gets the daddy bonus?: Organizational hegemonic masculinity and the impact of fatherhood on earnings’, Gender and Society. doi: 10.1177/0891243210386729.

-

Hill E, Baird M, Cooper R, Probyn E, Vromen A, Meers Z forthcoming ‘Young women and men: Imagined futures of work and family Fformation; Australian Journal of Sociology.

-

Investing in Women, An Initiative of the Australian Government (2019), “Why companies should advance parental leave.” Last accessed 6 June 2019: <https://investinginwomen.asia/posts/why-companies-should-advance- parental-leave/>.

-

Kalb, Guyonne. (2018) “Paid Parental Leave and Female Labour Supply: A Review”, Economic Record 94.304: 80–100.

-

Karu, M, and Tremblay, D. (2018), “Fathers on Parental Leave: An Analysis of Rights and Take-up in 29 Countries.” Community, Work & Family, 21.3: 344–362.

-

Martin, B. et al. (2014), “PPL Evaluation: Final Report” Institute for Social Science Research, accessed at: <https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/03_2015/finalphase4_report_6_ma rch_2015_0.pdf>.

-

McGinn, K.L. et al. (2018) “Learning from Mum: Cross-National Evidence Linking Maternal Employment and Adult Children’s Outcomes.” Work, Employment and Society.

-

McKinsey Global Institute, (2016), “The economic benefits of gender parity,” Last accessed 23 May 2019: <https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/overview/in-the- news/the-economic-benefits-of- gender-parity>.

-

Moran, J. and Koslowski, A, (2019), “Making Use of Work–family Balance Entitlements: How to Support Fathers with Combining Employment and Caregiving.” Community, Work & Family, 22.1: 111–128.

-

Ndzi, E. (2017) “Shared Parental Leave: Awareness Is Key.” International Journal of Law and Management 59.6: 1331–1336.

-

Norman, H., Elliot, M., and Fagan, C., (2018), “Does Fathers’ Involvement in Childcare and Housework Affect Couples’ Relationship Stability?” Social Science Quarterly 99.5: 1599–1613.

-

Norman, H., Fagan, C. & Elliot, M., (2017) ‘How can policy support fathers to be more involved in childcare? Evidence from cross-country policy comparisons and UK longitudinal household data’ Women and Equalities Committee.

-

O’Brien, M, (2013) “Fitting Fathers into Work-Family Policies: International Challenges in Turbulent Times.” The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 33.9/10: 542–564.

-

OECD (2017) Key Characteristics of Parental Leave Systems, OECD Family Database, accessed at <https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf>

-

Paid Parental Leave Act 2010, Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00299

-

Patnaik, A. (2019), ‘Reserving Time for Daddy: The Consequences of Fathers’ Quotas’, The Journal of Labor Economics, Forthcoming in October 2019.

-

Petts, Richard J., Knoester, Chris, and Li, Qi. (2018) “Paid Parental Leave-Taking in the United States.” Community, Work & Family: 1–22.

-

Pocock, B., Charlesworth, S., and Chapman, J., (2014), “Work-Family and Work- Life Pressures in Australia: Advancing Gender Equality in ‘Good Times’?” The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33.9/10, 594–612.

-

Rau, H. and Williams, J.C. (2017), “A Winning Parental Leave Policy can be Surprisingly Simple”, Harvard Business Review, accessed 12 June 2019, <https://hbr.org/2017/07/a-winning- parental-leave-policy-can-be-surprisingly- simple>.

-

Rehel, E.M. (2014) “When Dad Stays Home Too: Parental Leave, Gender, and Parenting.” Gender & Society 28.1: 110–132.

-

Skinner, Natalie, and Pocock, Barbara. (2013) “Paid Annual Leave in Australia: Who Gets It, Who Takes It and Implications for Work–life Interference.” Journal of Industrial Relations 55.5: 681–698.

-

Thébaud, S. & Halcomb, L. (2019) “One step forward? Advances and setbacks on the path toward gender equality in families and work” Sociology Compass, 13.6: 1- 15.

-

Valarino, I., and Gauthier, J. (2015), “Parental Leave Implementation in Switzerland: a Challenge to Gendered Representations and Practices of Fatherhood?” Community, Work & Family, 19.1: 1–20.

-

WGEA (2016), Agency Reporting Data (2015-16 reporting period).

-

WGEA (2018), Agency Reporting Data (2017-18 reporting period).

-

Fair Work Ombudsman, 2016, “Best practice guide parental leave” , Fair Work Ombudsman, accessed 29 August 2019, <file:///C:/Users/MB3855/Downloads/parental-leave-best-practice-guide.pdf>.

Quick guide - gender equitable parental leave (PDF, 399.38 KB)

This leading practice guide provides evidence based recommendations for creating more equitable parental leave policies.