Wages and Ages: Mapping the Gender Pay Gap by Age

Although Australian women enrol in and complete higher education and enter the labour market at a higher proportion than men, they are still substantially less likely to work full-time across all age groups and less likely to reach the highest earning levels.

The Wages and Ages: Mapping the Gender Pay Gap by Age data series is the first time WGEA data has been broken down by age to track these patterns.

This data shows the workforce inequalities where age and gender overlap, based on the 2021 WGEA employer census data.

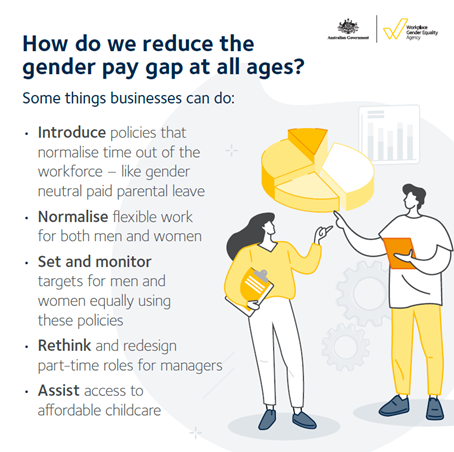

Actions to close the gender pay gap

Workplace policies and practices that address inequalities in pay and leadership and provide women and men more choice in managing paid and unpaid responsibilities are key to progressing workplace gender equality outcomes and eliminating gender differences in pay, employment status, and progression into leadership.

Important to this, employers should offer inclusive flexible working arrangements and rethink assumptions and norms around management roles.

An investment in gender equality is beneficial for employers as much as employees as it can attract and retain talent.

What employers can do

Employer actions for fostering a gender and age diverse workforce are:

1. Conduct a pay gap analysis

A critical step in taking action to address and improve pay equity in your organisation is to review the data and understand what is driving any gender pay gaps. The more detailed your analysis – for instance, by including employee manager/non-manager positions, employment status and age – the more you will be able to tailor a strategy and action plan to address your organisation’s specific issues.

2. Introduce a robust gender neutral paid parental leave policy

Parental leave policies are designed to support and protect working parents around the time of childbirth or adoption of a child and when children are young. The availability of paid parental leave for each parent fosters a more equal division of labour and can change gender norms about paid and unpaid responsibilities.

While 55% of organisations in WGEA’s 2020-21 dataset offered primary and secondary carer’s leave to both women and men, only 12% of men took primary carer’s leave. Therefore, employers have several options available that can encourage more gender balance in the uptake of parental leave. This includes encouraging more men to take parental leave and implementing gender-neutral parental leave policies that do not distinguish between primary and secondary carers. References to primary and secondary carers can continue gender roles and attitudes about the division of paid and unpaid responsibilities. Gender neutral parental leave policies can promote a model of shared care.

Other measures to consider are paying superannuation on parental leave in order to help address the gender superannuation gap and offering flexibility as to when parental leave can be taken following birth or adoption in order for the leave to complement the needs of the family and transitions to work and/or other childcare arrangements.[1]

3. Normalise flexible working arrangements

Flexible working arrangements are described as an agreement between an employer and an employee to change the standard working arrangement to better accommodate an employee’s commitments out of work. Flexible working arrangements usually encompass changes to the hours, pattern and location of work, and can be either formal or informal.

Women are more likely to request flexible working arrangements than men,[2] while men are more likely to have requests for flexible working arrangements refused.[3] Flexible working arrangements can be a critical enabler in providing both women and men more choice in managing paid and unpaid commitments, but first, employers must normalise their use by both women and men.

In addition, flexible work policies must be inclusive of workers of all ages, given that workers of all ages are balancing paid and unpaid responsibilities. Mature workers have reported fewer options for flexible working arrangements that meet their needs.[4]

Options for employers include:

- Formalising flexible working arrangements in policy

- Ensuring policies and strategies on flexible work are gender neutral and age neutral

- Implementing an all roles flex approach

- Promoting flexible working arrangements internally and have managers role model their use.

4. Rethink and redesign part-time roles for managers

Part-time work is a type of flexible working arrangement, where a regular work pattern that is less than full-time is established and an employee is paid on a pro-rata basis for that work. More women work part-time than men, yet the majority of manager roles are full-time.[5] This is not compatible with women’s overall employment status and can limit women’s career progression.

Employers must challenge norms and assumptions about leadership by thinking innovatively about management roles and progression into leadership. This includes offering part-time management opportunities and ensuring managers have access to other flexible work options. The share of part-time female managers increases when organisations implement a policy of formal support for flexible work and report their progress and statistics to their boards on these policies.[6] Research also demonstrates that, on average, companies with more part-time managers have more women at executive levels,[7] and more women in senior leadership improves company performance, productivity and profitability.[8]

5. Inclusive recruitment and promotion practices

Gender and age discrimination can be encountered by any employee at any point in the employment cycle.[9] This discrimination can impact on who is hired and progresses into leadership. Research finds that older job applicants were less likely to receive calls about their job applications, with older women having a lower rate of callbacks than men.[10] Age, either being too young or too old, can also act as a barrier to women being promoted.[11]

However, less than a quarter of organisations have recruitment practices that account for fostering an age diverse workforce, and a minority of organisations offers manager training on managing a multi-generational workforce.[12] In addition, HR workers participating in a survey thought that their organisations would be “reluctant” to recruit individuals above a certain age.[13]

Employers can take steps to minimise the impact of discrimination and bias on recruitment and promotion processes. This is important because gender diverse [14] and age diverse [15] teams can foster innovation.

During recruitment, employers can:

- Monitor and review the data on who is applying for jobs and who receives an interview invitation. Consider whether interview invitations are reproducing inequalities by excluding individuals based on gender and age (as well as other intersectional biases such as race, ethnicity, and disability).

- Ensure evaluation criteria to assess job applications is tied to the job, weighted and pre-determined so evaluators do not shift criteria to favour applicants who fit a stereotypical profile.

- Develop structured interview questions that are related to the job criteria and consider the candidate against that. Interviewers should also be trained to use ‘counter-stereotypical’ scenarios to question (either individually or collectively) how they react to candidate’s answers.

- Consider how you may be using anonymous recruitment procedures. Organisations need to be aware of the unintended consequences that can arise from anonymous recruitment procedures and conduct rigorous testing and evaluation to ensure that the process does not exacerbate existing inequalities. Organisations may wish to consider using anonymisation for procedures that test work performance (such as work sample tests or job-specific questionnaires), rather than anonymising resumes.

During promotion, employers can:

- Train managers to provide specific feedback. Women are more likely to receive feedback that is vague and unspecific, such as being told they are ‘too abrasive’ or ‘too demanding’. Managers must be trained to provide feedback that is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, timely and thoughtful.

- Develop employee careers. Employers must seek to ensure equal opportunities for career development are available. Managers should also be given specific guidance on how to avoid letting gender-based and age-based assumptions interfere with the allocation of career development opportunities.

- Value alternative leadership styles. Organisations should develop new evaluation frameworks to ensure that alternative leadership styles and innovative parameters for leadership positions are equally valued and respected. This can include more options for part-time manager roles and valuing flexible working arrangements at all levels of the organisation. This can help to ensure that women progress into more senior roles at the same rate as men.

6. Support training and transitions

Some employers have non-leave based measures that support employees with children and caring responsibilities, especially when parents are first returning to work after a period of leave. This may include referral services, support networks, childcare supports, and stay-in-touch programs to support employee connection with the workplace while on leave and transition back to the workplace.[16] As new parents return to work, some leading practice employers offer coaching on how to manage professional and personal commitments.[17]

More mature workers may also benefit from training as people work for longer and re-enter the workforce at older ages. This includes training on newer technologies and upskilling that can counteract negative biases and perceptions that individuals have about more mature workers.[18] In addition, employers can assist mature workers in identifying relevant and transferable skills and provide training where workers may be leaving an employer for a reason besides voluntary retirement.[19]

What employees can do

Use WGEA’s interactive data visualiser to search your company, see their policies and practices they report.

When considering job offers, see how the workplace compare on the availability of paid parental leave, gender balance in leadership, or if the company takes action on gender equality through regular pay audits.

WGEA Resources

WGEA Data Explorer: displays gender pay gap data (based on a census of non-public sector organisations with 100 or more employees that are required to report to the Agency and representing over 40% of Australian employees)

Parental leave: research and guides on designing equitable parental leave policies

Flexible work: information and toolkits for mainstreaming flexible working arrangements

Leadership: research and tools for progressing women into positions of leadership

Recruitment and promotion: research and guide on addressing gender discrimination and bias in recruitment and promotion processes.

References

Reference List

- Fitzsimmons, TW, Yates, MS & Callan, VJ (2020), Employer of Choice for Gender Equality: Leading practices in strategy, policy and implementation, Brisbane: AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

- WGEA (2016), Unpaid care work and the labour market, viewed 16 June 2022, available: https://www.wgea.gov.au/publications/unpaid-care-work-and-the-labour-market.

- Sanders, M, Zenga, J Hellicar, M & Fagg K (2016), The power of flexibility: A key enabler to boost gender parity and employee engagement, Bain & Co, viewed 23 June 2022, available: https://www.bain.com/insights/the-power-of-flexibility/.

- Andrei, D, Parker, S, Constantin, A, Baird, M, Iles, L, Petery, G, Zoszak, L, Williams, S & Chen, S (2019), Maximising potential: Findings from the Mature Workers in Organisations Survey (MWOS), ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research, viewed 17 June 2022, available: https://matureworkers.cepar.edu.au/p/maximising-potential-findings-from-the-mature-workers-in-organisations-survey-mwos/.

- WGEA (2022), The gender pay gap by age group.

- Cassells, R & Duncan, A (2019), Gender Equity Insights 2019: Breaking through the Glass Ceiling, BCEC | WGEA Gender Equity Series, Issue #4, March 2019.

- Cermak, J, Howard, R, Jeeves, J & Ubaldi, N (2017), Women in Leadership: Lessons from Australian Companies Leading the Way, McKinsey & Co, Business Council Australia, WGEA, viewed 21 December 2020, available: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/Gender%20Equality/Women%20in%20leadership%20Lessons%20from%20Australian%20companies%20leading%20the%20way/Women-in-Leadership-Lessons-from-Australian-companies-leading-the-way.pdf.

- Cassells, R & Duncan, A (2021), Gender Equity Insights 2021: Making it a priority, BCEC|WGEA Gender Equity Series, Issue #6, March 2021.

- Australian Human Rights Commission (2021), What’s age got to do with it?, viewed 17 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/publications/whats-age-got-do-it-2021; WGEA (n.d.), Recruitment and promotion, viewed 15 June 2022, available: https://www.wgea.gov.au/recruitment-and-promotion.

- Zucker, R (2019), Ageism in a job interview, Harvard Business Review, viewed 9 June 2022, available: https://hbr.org/2019/08/5-ways-to-respond-to-ageism-in-a-job-interview.

- Cleveland, JN, Huebner, L-A, & Hanscom, ME (2017), The Intersection of Age and Gender Issues in the Workplace, Age Diversity in the Workplace, Advanced Series in Management, vol. 17, pp. 119-137, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, https://doi.org/10.1108/S1877-636120170000017007.

- Australian Human Rights Commission and Australian HR Institute (2021), Employing and retaining older workers, viewed 8 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/ahri_employingolderworkers_april_2021.pdf.

- Australian Human Rights Commission and Australian HR Institute (2021), Employing and retaining older workers, viewed 8 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/ahri_employingolderworkers_april_2021.pdf.

- WGEA (2018), Workplace gender equality: the business case, viewed 17 June 2022, available: https://www.wgea.gov.au/publications/gender-equality-business-case#org-performance.

- Bersin, J & Chamorro-Premuzic, T (2019), The case for hiring older workers, Harvard Business Review, viewed 15 June 2022, available: https://hbr.org/2019/09/the-case-for-hiring-older-workers.

- WGEA (2022), WGEA Data Explorer, viewed 17 June 2022, available: https://data.wgea.gov.au/home; Fitzsimmons, TW, Yates, MS & Callan, VJ (2020), Employer of Choice for Gender Equality: Leading practices in strategy, policy and implementation, Brisbane: AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

- See Fitzsimmons, TW, Yates, MS & Callan, VJ (2020), Employer of Choice for Gender Equality: Leading practices in strategy, policy and implementation, Brisbane: AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

- For discussion on these biases, see Australian Human Rights Commission (2016), Willing to work: National Inquiry into Employment Discrimination against Older Australians and Australians with Disability, viewed 8 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/publications/willing-work-national-inquiry-employment-discrimination?_ga=2.72697491.140858695.1654043163-688958571.1653361685; Australian Human Rights Commission (2021), What’s age got to do with it?, viewed 17 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/publications/whats-age-got-do-it-2021.

- Australian Human Rights Commission (2016), Willing to work: National Inquiry into Employment Discrimination against Older Australians and Australians with Disability, viewed 8 June 2022, available: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/publications/willing-work-national-inquiry-employment-discrimination?_ga=2.72697491.140858695.1654043163-688958571.1653361685.